Learning from Lockdown: Don’t blame density for problems caused by poverty, writes Earle Arney

Good health and housing should not just be the privilege of the wealthy

One of the vilest legacies of the pandemic is its disproportionate impact on the urban poor. But while health , and housing must be united to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable groups, what can we learn from COVID-19? And how do we separate fact from fiction in the centuries old debate between density and its links to vulnerability to infectious disease?

As shapers of cities, our first task as we emerge from the pandemic is to radically improve our care and consideration of the vulnerable. But what we must also do is guard against Dickensian reactions to population density in our cities.

Fears around density have long shaped our cities. Ever since Charles Dicken's penned his many works laying bare the startling living conditions of the Victorian urban poor, density has becomes shackled with notions of poor health and disease in urban society.

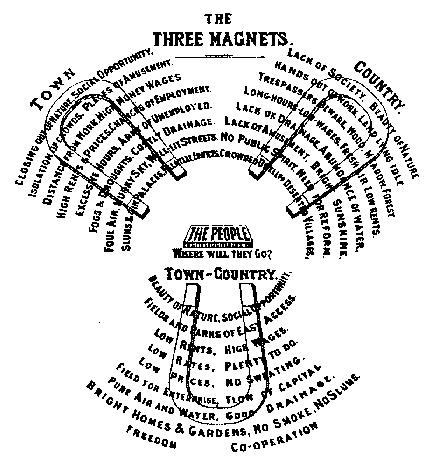

Ebeneezer Howard’s 1890s Garden City Movement was built on these fears, harnessing the bucolic beauty and promise of the sanctuary of the suburbs to persuade a generation to escape the growing Victorian industrial cities to a better rural life. The Garden City movement advocated ‘building-out’ with extremely low density cities offering the very best of urban and rural life combined, an idea that is experiencing something of a renaissance today.

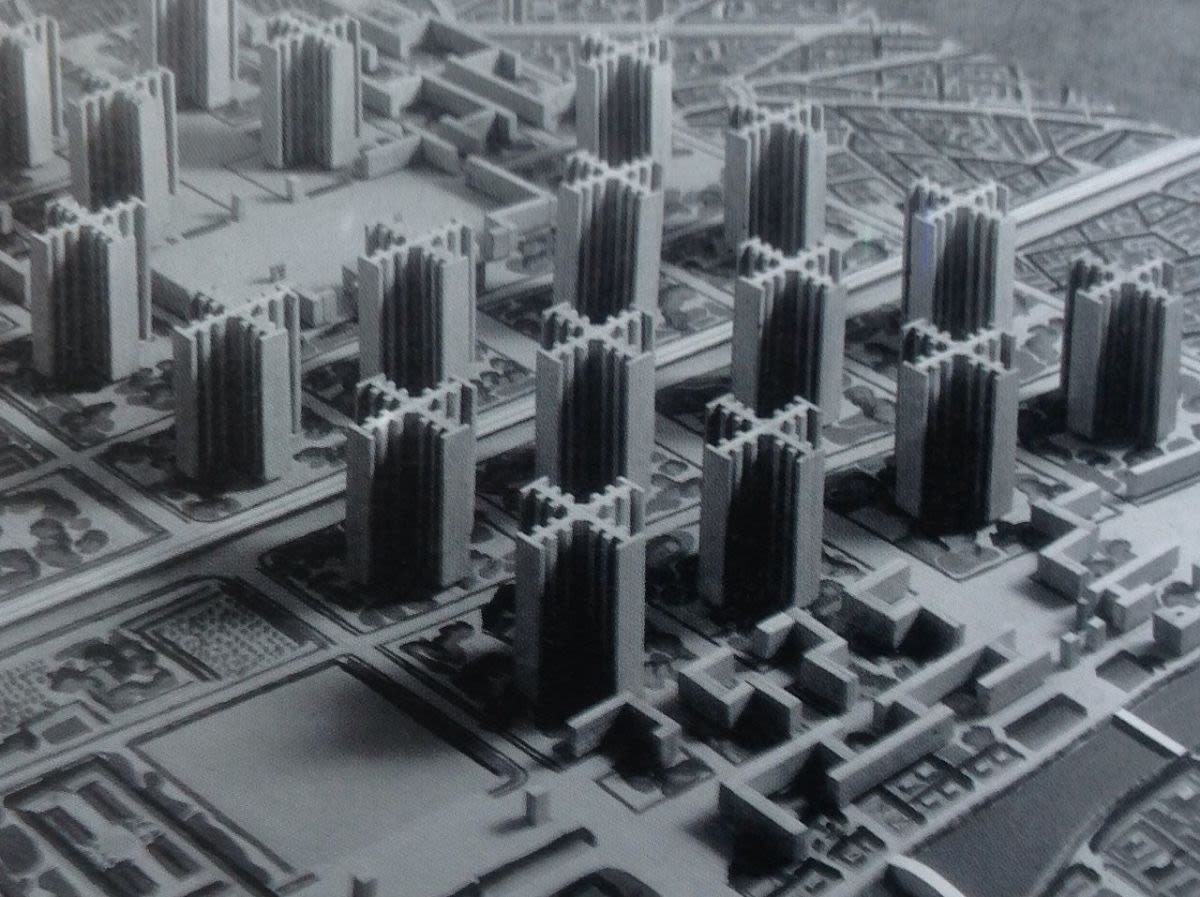

Modernism, while less overt in its anti-density narrative, emerged with a clear social purpose to remedy the problems of urban living, such as sorry living conditions and overcrowding of the urban poor in many cities. Modernism was also set against a backdrop of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. The ideas of the movement are most memorably manifest by Le Corbusier in his proposals for cities such as Paris, where the dense and intricate street patterns are swept away in favour of ‘building-up’ with disconnected high rise towers in acres of space.

Although density has a role in defining the health and happiness of our cities, it has become the fall guy for wider urban problems. High density is not inherently 'bad', just as low density is not inherently 'good'. If density is the defining factor in whether cities are ‘healthy’ and resilient, then what about Singapore, Seoul and Shanghai? All are extremely high density, yet fared much better during the current pandemic than some of their less dense counterparts.

At a recent seminar hosted by AFK, Dr Sameh Wahba, Global Director for the World Bank, debunked the misunderstood correlation between vulnerability to COVID-19 and urban density. Wahba’s team investigated 284 Chinese cities and published research that suggests a mutually inclusive link between population density and disease is unfounded. He also used the data currently available for New York City to illustrate that in some urban areas, COVID-19 cases are disproportional to urban density. For example, Manhattan, the most populous borough of New York City, had at that time, fewer cases of COVID-19 compared to the less densely populated outer suburban boroughs of Queens and Staten Island.

... if density is the defining factor in whether cities are ‘healthy’ and resilient, then what about Singapore, Seoul and Shanghai? All are extremely high density, yet fared better during the pandemic than some of their less dense counterparts.Earle Arney, CEO and Founding Director, AFK

Wahab's team's data found evidence that higher-density cities are not necessarily more vulnerable - and lower-density cities more resilient - to the pandemic. Moreover, Dr Wahba wrote that “higher densities, in some cases, can even be a blessing rather than a curse in fighting epidemics. Due to economies of scale, cities often need to meet a certain threshold of population density to offer higher-grade facilities and services to their residents” to help protect against the transmission of disease.

So if density isn’t to blame, what makes one city more vulnerable than the next?

It is simple - poverty. Covid has had a disproportional effect on the urban poor, who have suffered greatly during the pandemic. London, to its great shame, has shocking rates of urban poverty peppered throughout its boroughs. According to London’s Poverty Profile , poverty rates are higher for London than in any other region of the UK. Similarly, it is critical that health and housing goes hand in hand if we are to break the cycle, as pointed out by the former head of the UK Civil Service, Lord Kerslake in Building Design , higher death rates to COVID-19 in London were also in areas where the housing need is the most acute and overcrowding rife.

But what is also key to understand, is this is not a problem of high density alone - but the addition of abject poverty. After all, if this was the case then how could some of London’s most desirable and affluent boroughs which are also the most dense, still have the lowest COVID-19 cases in the city?

Post-pandemic, after many months of isolation and avoiding proximity, we must avoid engaging in same negative circular narrative on density, which could rekindle a revival of interest in anti-urban utopias, and perhaps even the rebirth of urban sprawl.

We must also begin to begin to tackle the problems and legacy of the pandemic on the urban poor. A first step is to ensure that affordable housing targets are not lowered. We just need to get on and deliver them at a good level of density. Given the economic impact of Coronavirus, special development authorities should be established to deliver this much needed essential resource quickly. Think of the Olympic Delivery Authority that effectively delivered mass housing within a compressed time period – something we have otherwise been incapable of as a nation since the post-war period.

This extreme health and housing crisis requires extreme action. It’s time to accept that the system is not working. These new special development authorities must sit outside our broken planning and local political system and be empowered to deliver homes across GLA defined Brownfield Sites, Opportunity Areas and Housing Zones – all within a defined sun-set. Such a bold move would be highly effective in offsetting the impacts of coronavirus by speeding up housing delivery before more poor people unnecessarily die.

The quantum of houses is only the base of Maslow’s pyramid – we must also address the quality of homes. Residential space standards now need to be updated to ensure adequate provision for homeworking and associated qualitative measures such as acoustics. Our standards should enshrine the provision of flexible spaces that are truly suitable for working, while converting to a more homely space when required. Further, permitting the entirety of open space provisions to be provided in communal areas without any such provision being directly associated with apartments must be a thing of the past. As architects we know that such apartments can be achieved with minimal uplift in area and no increase in external wall.

Delivering good quality Affordable homes fit for their evolving purpose should be accompanied by an increased emphasis on access to green space. Existing green space including the Greenbelts, must be preserved and nurtured. A recent study for the GLA has found that Londoners avoid £950 million per year in costs to the NHS thanks to public green space; £580m from being in better physical health and £370m from better mental health. Delivering homes for the urban poor is paramount. As a UK national who has spent much of my life living outside our Kingdom, I find it extraordinary that our industry has yet to find its voice in demanding change and we persist with a quiet acceptance of our industries lack of progress in delivery housing for the urban poor. Housing matters.

We can get the development economics to balance by increasing density to offset the provision of Affordable homes. As the World Bank has proven, it’s the quality of homes that matter and in the UK, getting on and providing them is what we need to get sorted.

We should instead use our knowledge that density can be unshackled from disease to spark not the death of our cities but their rebirth - with good housing for all.

The oroginal published version of this article appeared in Building Design and can be read in full here